How often do rehabilitation programs ignore the unique demands of a specific sport?

In all my sports performance jobs, I have had some sort of role in the return-to-play process for a variety of injuries both short-term and long-term. From what I have encountered, most rehabilitation protocols stay way too generic for too long. They begin to take into account the unique demands of a particular sport only after losing a crucial amount of time. This results in an unnecessarily extended process that often includes extraneous activity – which may look like rehab but in actuality it isn’t getting us any closer to the end goal

For the majority of rehabilitation protocols that I’ve seen, the switch to what looks like more specificity should happen much earlier on in the process than what most generic timelines dictate. If you are rehabbing the athletes to return to their sport, you need to have the demands of that sport in mind the entire time you are rehabbing the injury. Depending on the severity of the injury, early-stage rehab could be very basic and that is perfectly appropriate (first 12 weeks of ACL, first 16 weeks of Achilles, etc). But there comes a time in the process where the graft/repair/injury site is past a certain danger zone and the road to playing again, physically, simply involves getting the tissues back to handling the load required by the sport. This is the point where most rehab could improve and where we at UMass feel we are doing progressive work.

No matter the injury, you must start the rehabilitation process by identifying the desired end result: what kind of performance are you getting the athlete back to? In a sports setting the obvious answer is to, “play their sport,” but you’ll need to go beyond that vague answer and identify what the specific demands are -- similar to the process that should take place for any physical preparation program. For example almost all field-sports require first derivative movements such as full-speed sprinting, jumping, and cutting. So, if you have identified these movements as the end goal, any portion of rehabilitation that isn’t getting the athlete closer to that is, at best, a waste of time and, at worst, detrimental to the process. For the purposes of this article, I’m going to stick to lower body injuries where the main end goal is an athlete’s return to the locomotion mentioned above.

General Strength and Ground Contacts

Once you’ve identified the end goal, you can then identify the main impediment to that goal. We like to think of KPIs as both key performance inhibitors and key performance indicators. For medium to long-term lower body injuries the limitation is often rooted in elasticity or the inability to handle high-speed loading and ground contact. The building of general strength and the building of elasticity are two separate endeavors and should not be treated as sequential. In conjunction with a general strength training plan, our number one aim is to start introducing ground contacts as soon as possible, however low threshold they need to be. The gradual scaling up of ground contact volumes and intensities, in ways that build elasticity, is paramount.

Waiting to introduce ground contacts until general strength or girth measurements are at a certain threshold – which is often arbitrary – will prolong the rehabilitation process dramatically. If you are using this delayed approach thinking it will improve your ability to handle ground contact, you will be sorely disappointed the first time that your athletes go to run. If you are waiting until general strength is built thinking that ground contacts are unsafe before that point, you are underestimating your own ability to scale contacts.

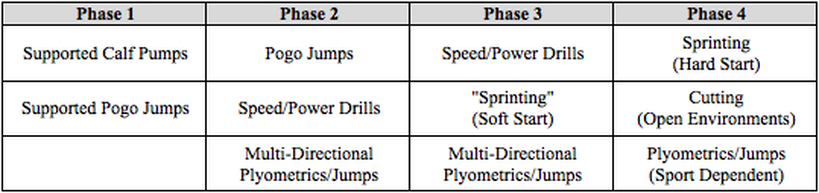

When first introducing ground contact, we start with supported calf pumps, not even a true contact. They essentially look like a pogo jump where the ball of your foot stays on the ground, or as the name implies, a really fast and rhythmic calf raise. We’ve only had to stick with those for a few days to a week until moving onto supported pogo jumps. With the support and extensive nature of both of these first two progressions, we are able to keep both volume and frequency decently high (60-80 daily contacts, 3-5x/wk).

As support needed on the pogo jumps decreases, eventually that seamlessly rolls into being able to perform unsupported pogo jumps. Deciding exactly when the athlete is ready for this progression is subjective as we are simply watching and evaluating how they go about interacting with the ground and their level of stiffness. (I suppose you certainly could get into objectively measuring this with a contact mat or force plate but I have never been in a situation where those were available so I’ll leave that for someone else to write about.) When the athlete reaches the point of being able to move to unsupported pogo jumps, both frequency and volume will come down slightly (40-60 contacts, 2-3x/wk). Also at this milestone, we introduce speed/power drills and various skipping variations (e.g. 2-3x/wk of build-up dribbles, A-skips, and vertical power skips at an “as tolerated” intensity for 50-100 total yards). As the intensity of speed/power drills approaches full-speed, the drills easily roll into the introduction of “sprinting.”

Introduction to Sprinting

When I mentioned starting to introduce ground contact earlier, I made sure to include “in ways that build elasticity.” This is an important distinction to note if you are making sure to keep your end goal and therefore, your key performance inhibitors, in mind. When working back to full-speed sprinting, jumping, and cutting, we do not allow the athlete to perform any running below approximately 70% sprint speed. Any running that takes place should have similar ground interactions and attain similar shapes to full-speed sprinting. Just because the athlete is allowed to start running does not mean that they should. Remember, the end goal is to sprint -- not run -- and running does not prepare you to sprint.

The athlete should never be prescribed locomotion that promotes heel striking. If an athlete is cleared to run and the progression to sprinting is running at 40% speed for a given timeframe and then 50% for a given timeframe and so on and so forth, they are performing activity that is not in any way getting them closer to returning to their sport. As mentioned above, in order to get an athlete to the point where they can handle the speeds and forces associated with sprint-like running and then eventually sprinting, we build up the volumes and intensities of speed/power drills until it rolls into the running shapes we are looking for.

When rehab programs use soft starts and avoid any forced deceleration, athletes return to sprinting, interact with ground at a much higher quality, and get into proper shapes, much sooner than most would assume. For reference, with a full Achilles rupture repair we were able to follow this progression of supported pogo jumps at 5 months post-op, unsupported pogo jumps and speed/power drills at 5.5 months post-op, introduction to “sprinting” at 6 months post-op, and unrestricted full-speed sprinting from a hard start at 7 months post-op.

Currently working with two ACL repairs in our athletes, we introduced the supported pogo jumps at 4.5 months post-op, unsupported pogo jumps and speed/power drills at 5 months post-op, and we introduced “sprinting” at 5.5 months post-op. Both were at full speed sprinting by the end of our winter block and had no trouble with high intensity multi-directional plyometrics (6 months post-op). The timeline for both would have been bumped up 4 weeks (supported pogo jumps at 3.5 months post-op progressing to full speed sprinting at 5 months post-op) but unfortunately that was the start of winter break and we didn’t feel comfortable having them start that process unsupervised at home.

The ACL repairs are still a work in progress, but there is notable progress with the Achilles. Building the athlete up to tolerate ground contacts under 0.1 seconds (sprinting) prepared him to better handle the slower ground contacts incurred during cutting and deceleration, when it was introduced. All cutting and deceleration work progressed at an accelerated rate as a result of the stiffness and resilience to high-speed loading that was built through the reintroduction to full-speed sprinting.

In all my sports performance jobs, I have had some sort of role in the return-to-play process for a variety of injuries both short-term and long-term. From what I have encountered, most rehabilitation protocols stay way too generic for too long. They begin to take into account the unique demands of a particular sport only after losing a crucial amount of time. This results in an unnecessarily extended process that often includes extraneous activity – which may look like rehab but in actuality it isn’t getting us any closer to the end goal

For the majority of rehabilitation protocols that I’ve seen, the switch to what looks like more specificity should happen much earlier on in the process than what most generic timelines dictate. If you are rehabbing the athletes to return to their sport, you need to have the demands of that sport in mind the entire time you are rehabbing the injury. Depending on the severity of the injury, early-stage rehab could be very basic and that is perfectly appropriate (first 12 weeks of ACL, first 16 weeks of Achilles, etc). But there comes a time in the process where the graft/repair/injury site is past a certain danger zone and the road to playing again, physically, simply involves getting the tissues back to handling the load required by the sport. This is the point where most rehab could improve and where we at UMass feel we are doing progressive work.

No matter the injury, you must start the rehabilitation process by identifying the desired end result: what kind of performance are you getting the athlete back to? In a sports setting the obvious answer is to, “play their sport,” but you’ll need to go beyond that vague answer and identify what the specific demands are -- similar to the process that should take place for any physical preparation program. For example almost all field-sports require first derivative movements such as full-speed sprinting, jumping, and cutting. So, if you have identified these movements as the end goal, any portion of rehabilitation that isn’t getting the athlete closer to that is, at best, a waste of time and, at worst, detrimental to the process. For the purposes of this article, I’m going to stick to lower body injuries where the main end goal is an athlete’s return to the locomotion mentioned above.

General Strength and Ground Contacts

Once you’ve identified the end goal, you can then identify the main impediment to that goal. We like to think of KPIs as both key performance inhibitors and key performance indicators. For medium to long-term lower body injuries the limitation is often rooted in elasticity or the inability to handle high-speed loading and ground contact. The building of general strength and the building of elasticity are two separate endeavors and should not be treated as sequential. In conjunction with a general strength training plan, our number one aim is to start introducing ground contacts as soon as possible, however low threshold they need to be. The gradual scaling up of ground contact volumes and intensities, in ways that build elasticity, is paramount.

Waiting to introduce ground contacts until general strength or girth measurements are at a certain threshold – which is often arbitrary – will prolong the rehabilitation process dramatically. If you are using this delayed approach thinking it will improve your ability to handle ground contact, you will be sorely disappointed the first time that your athletes go to run. If you are waiting until general strength is built thinking that ground contacts are unsafe before that point, you are underestimating your own ability to scale contacts.

When first introducing ground contact, we start with supported calf pumps, not even a true contact. They essentially look like a pogo jump where the ball of your foot stays on the ground, or as the name implies, a really fast and rhythmic calf raise. We’ve only had to stick with those for a few days to a week until moving onto supported pogo jumps. With the support and extensive nature of both of these first two progressions, we are able to keep both volume and frequency decently high (60-80 daily contacts, 3-5x/wk).

As support needed on the pogo jumps decreases, eventually that seamlessly rolls into being able to perform unsupported pogo jumps. Deciding exactly when the athlete is ready for this progression is subjective as we are simply watching and evaluating how they go about interacting with the ground and their level of stiffness. (I suppose you certainly could get into objectively measuring this with a contact mat or force plate but I have never been in a situation where those were available so I’ll leave that for someone else to write about.) When the athlete reaches the point of being able to move to unsupported pogo jumps, both frequency and volume will come down slightly (40-60 contacts, 2-3x/wk). Also at this milestone, we introduce speed/power drills and various skipping variations (e.g. 2-3x/wk of build-up dribbles, A-skips, and vertical power skips at an “as tolerated” intensity for 50-100 total yards). As the intensity of speed/power drills approaches full-speed, the drills easily roll into the introduction of “sprinting.”

Introduction to Sprinting

When I mentioned starting to introduce ground contact earlier, I made sure to include “in ways that build elasticity.” This is an important distinction to note if you are making sure to keep your end goal and therefore, your key performance inhibitors, in mind. When working back to full-speed sprinting, jumping, and cutting, we do not allow the athlete to perform any running below approximately 70% sprint speed. Any running that takes place should have similar ground interactions and attain similar shapes to full-speed sprinting. Just because the athlete is allowed to start running does not mean that they should. Remember, the end goal is to sprint -- not run -- and running does not prepare you to sprint.

The athlete should never be prescribed locomotion that promotes heel striking. If an athlete is cleared to run and the progression to sprinting is running at 40% speed for a given timeframe and then 50% for a given timeframe and so on and so forth, they are performing activity that is not in any way getting them closer to returning to their sport. As mentioned above, in order to get an athlete to the point where they can handle the speeds and forces associated with sprint-like running and then eventually sprinting, we build up the volumes and intensities of speed/power drills until it rolls into the running shapes we are looking for.

When rehab programs use soft starts and avoid any forced deceleration, athletes return to sprinting, interact with ground at a much higher quality, and get into proper shapes, much sooner than most would assume. For reference, with a full Achilles rupture repair we were able to follow this progression of supported pogo jumps at 5 months post-op, unsupported pogo jumps and speed/power drills at 5.5 months post-op, introduction to “sprinting” at 6 months post-op, and unrestricted full-speed sprinting from a hard start at 7 months post-op.

Currently working with two ACL repairs in our athletes, we introduced the supported pogo jumps at 4.5 months post-op, unsupported pogo jumps and speed/power drills at 5 months post-op, and we introduced “sprinting” at 5.5 months post-op. Both were at full speed sprinting by the end of our winter block and had no trouble with high intensity multi-directional plyometrics (6 months post-op). The timeline for both would have been bumped up 4 weeks (supported pogo jumps at 3.5 months post-op progressing to full speed sprinting at 5 months post-op) but unfortunately that was the start of winter break and we didn’t feel comfortable having them start that process unsupervised at home.

The ACL repairs are still a work in progress, but there is notable progress with the Achilles. Building the athlete up to tolerate ground contacts under 0.1 seconds (sprinting) prepared him to better handle the slower ground contacts incurred during cutting and deceleration, when it was introduced. All cutting and deceleration work progressed at an accelerated rate as a result of the stiffness and resilience to high-speed loading that was built through the reintroduction to full-speed sprinting.

Reintroduction to Cutting and Deceleration

Plyometrics/jumps that are multi-directional extensive, and working to intensive, were introduced in conjunction with the intensive speed/power drills and sprinting but we did not introduce any true cutting until full-speed sprinting was attained. Just like with the running/sprinting argument, if we start with slowed down cutting and work up faster, the slowed down work is not helping us achieve our end goal because the reduction in speed limits the exercise’s impact on elasticity. Instead, we choose to introduce non-linear loading to the tissues through multi-directional plyometrics/jumps which, combined with full speed sprinting, flows well into scaled down open environments which can be expanded out to increase the speed. Making this decision with any cutting work meant that when it was finally introduced in the Achilles rehabilitation process, the timeline from introduction to full-speed with no restrictions was only about 3 weeks.

Slowed down running and change of direction is not inherently detrimental to the athletes’ recovery. However, if physical activity is not directly building the qualities we want -- or is not directly supporting the work that we are doing to build the target qualities -- it is adding unneeded noise to the system. Too much noise will dampen the signal.

Conclusion

All physical preparation, including rehabilitation, must start with an analysis of the demands of the game. This allows for clear goals in the training process. Keeping the end goal in mind during the entire rehabilitation process helps avoid unneeded work that isn’t progressing the athlete back to playing the sport at full-speed. It’s easy to get excited and caught up in milestone moments along the way of “being cleared to run” or “being cleared to cut” and to immediately start doing those things at a slowed-down pace. But keep in mind: running isn’t the goal. Cutting around cones at 50% speed isn’t the goal. While it may give a short-term psychological boost, it does not get the athlete closer to what they actually care about, which is playing their sport. Start with the sport. Reverse engineer the requirements. Plan accordingly.

Acknowledgements

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention Boo Schexnayder, legendary track and field coach, and Arno Rheinberger, Director of Rehabilitation for Minnesota Football, as both have had a tremendous impact on my approach to this topic. Both are incredible resources on anything related to physical preparation.

Joel Reinhardt

Twitter: @joelreinhardt

Instagram: @joelhreinhardt

Email: [email protected]

Website: sprint-jump-throw.com

Plyometrics/jumps that are multi-directional extensive, and working to intensive, were introduced in conjunction with the intensive speed/power drills and sprinting but we did not introduce any true cutting until full-speed sprinting was attained. Just like with the running/sprinting argument, if we start with slowed down cutting and work up faster, the slowed down work is not helping us achieve our end goal because the reduction in speed limits the exercise’s impact on elasticity. Instead, we choose to introduce non-linear loading to the tissues through multi-directional plyometrics/jumps which, combined with full speed sprinting, flows well into scaled down open environments which can be expanded out to increase the speed. Making this decision with any cutting work meant that when it was finally introduced in the Achilles rehabilitation process, the timeline from introduction to full-speed with no restrictions was only about 3 weeks.

Slowed down running and change of direction is not inherently detrimental to the athletes’ recovery. However, if physical activity is not directly building the qualities we want -- or is not directly supporting the work that we are doing to build the target qualities -- it is adding unneeded noise to the system. Too much noise will dampen the signal.

Conclusion

All physical preparation, including rehabilitation, must start with an analysis of the demands of the game. This allows for clear goals in the training process. Keeping the end goal in mind during the entire rehabilitation process helps avoid unneeded work that isn’t progressing the athlete back to playing the sport at full-speed. It’s easy to get excited and caught up in milestone moments along the way of “being cleared to run” or “being cleared to cut” and to immediately start doing those things at a slowed-down pace. But keep in mind: running isn’t the goal. Cutting around cones at 50% speed isn’t the goal. While it may give a short-term psychological boost, it does not get the athlete closer to what they actually care about, which is playing their sport. Start with the sport. Reverse engineer the requirements. Plan accordingly.

Acknowledgements

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention Boo Schexnayder, legendary track and field coach, and Arno Rheinberger, Director of Rehabilitation for Minnesota Football, as both have had a tremendous impact on my approach to this topic. Both are incredible resources on anything related to physical preparation.

Joel Reinhardt

Twitter: @joelreinhardt

Instagram: @joelhreinhardt

Email: [email protected]

Website: sprint-jump-throw.com