For anyone that is familiar with the Feed the Cats system they know that a priority is put on the highest of quality sprint training at the lowest minimal effect dose. On days you are not sprinting, you are completing X-Factor workouts that are also a minimal dose of high-quality plyometric outputs, as well as what most people would consider speed-power or sprint form drills. The priority is training with high focus, therefore high quality, every time you train. As a part of our "Feed the Cats Soccer Roundtable" we spoke with Coach Tony Holler about his opinion on how the Feed the Cats philosophy would apply to a high-volume alactic-aerobic field sport. I begin the episode presenting the GPS data that I've utilized in my current position to drive decision making.

In my opinion, the most important thing to consider when designing, implementing, and modifying any physical loading is the requirements of the sport, the tactics of the coach you are working with, and the abilities of the athletes. I will cover mostly just the requirements of the sport and how that can provide guidance for the bioenergetic and biomotor skills of the athletes, which ultimately support the coach to get the desired outcome within their tactical training.

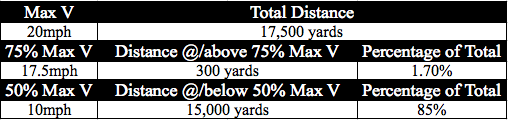

When looking at the game data, I saw that, on average, our high-minutes players covered about 9 to 10 miles in a game, which is about 17,500 yards. Of those 17,500 yards on average about 300 of those yards were registered at 75% or greater of each athlete’s individual max velocity - that is equivalent to 1.7% of the total distance covered in the game. Accounting for variation we can say that 97% of every single player's distance covered was completed at less than 75% of their relative max velocity. To dig even deeper, the average percentage of total distance covered below 50% of relative max velocity accounted for 85% of the games distance - that is roughly 15,000 of the 17,500 yards. To use round numbers, let’s say there's an athlete whose max velocity is 20 mph - 85% of that athlete’s total distance covered in the game was at or below 10 mph and only 3% of the total distance covered was at or greater than 17.5 mph.

In my opinion, the most important thing to consider when designing, implementing, and modifying any physical loading is the requirements of the sport, the tactics of the coach you are working with, and the abilities of the athletes. I will cover mostly just the requirements of the sport and how that can provide guidance for the bioenergetic and biomotor skills of the athletes, which ultimately support the coach to get the desired outcome within their tactical training.

When looking at the game data, I saw that, on average, our high-minutes players covered about 9 to 10 miles in a game, which is about 17,500 yards. Of those 17,500 yards on average about 300 of those yards were registered at 75% or greater of each athlete’s individual max velocity - that is equivalent to 1.7% of the total distance covered in the game. Accounting for variation we can say that 97% of every single player's distance covered was completed at less than 75% of their relative max velocity. To dig even deeper, the average percentage of total distance covered below 50% of relative max velocity accounted for 85% of the games distance - that is roughly 15,000 of the 17,500 yards. To use round numbers, let’s say there's an athlete whose max velocity is 20 mph - 85% of that athlete’s total distance covered in the game was at or below 10 mph and only 3% of the total distance covered was at or greater than 17.5 mph.

An important observation to make is that the majority of high-speed distance and big-time plays occur during plays in which the athlete is pursuing the ball, whether a forward moving to open space on offense or a back closing the gap to make a big defensive stop. Regardless of how technically sound an athlete is with the ball their ability to express true max velocity will not be attained with the ball at their foot. From that you can see the importance of linear sprint training, which can improve the potential to apply sporting movements at a higher velocity and creating a speed reserve.

As we can see, the average soccer player, and most other field-sport athletes, need to develop tissue tolerance to the external loads that will be placed on their body during competition. In order to develop the game-breaker qualities in speed and power as well as prepare them for all of the low-speed volume required to compete, training must be logically programmed, implemented, and managed. I specifically used the term low-speed volume because that does not mean it is low intensity. From watching a player, instead of just the game, you will observe many times that the athlete will continuously be shuffling side-to-side, slowly backpedaling, or even giving a valet jog while the ball is not close to them, but still maintaining the tactically advantageous position - those could be considered as low intensity because there is no pressure. Most plays made with the ball in which an opponent is directly pressing them require explosive touches on the ball, a few steps into open space, and then executing some sort of pass or shot. Those plays are certainly high intensity, however looking at the GPS data and not watching the player, all you would see is that they completed some sort of movement at 50% of their max velocity.

In small group and individual training in which technical skills are developed it is important that skills are practiced at a high intensity for seven seconds or less and then rest is provided such that the next rep of the skill is at the same quality. The beautiful thing about coaching is that if the skill is not being executed at the highest level, as expected in a game, you can stop the drill, provide feedback and enough rest so that the next attempt can done be at a higher quality. If fatigue is truly the limiting factor you have found your stopping point.

Many coaches utilize rondos and small-sided games for the technical and tactical development of their players. Most of those do a great job at providing the explosive efforts and sub 75% of relative max velocity speed demands required in a game (depending on constraints). The same guidelines can be provided to these drills, meaning that if the quality of the technical and tactical skills are not completed at a game-like level, stop the drill provide rest and feedback, and restart if it is desired. The nice thing about this style of drills is that there is the continuous, “flowy” type of play that is similar to competition.

There is obviously a tremendous amount of value in the development and execution of technical and tactical skills during these games, most even provide a supramaximal bioenergetic demand compared to competition averages. Competition averages are just that - averages. The distance-per-minute of a rondo or small-sided game may be 10 to 20% greater than the competition average, meaning it may actually touch the peak distance-per-minute attained during game for a small period of time. That is important for the preparation as well as the development of the bioenergetic demands of the sport, which certainly raise the heart rate to a point past the anaerobic threshold. Like many of our readers know, continuous training day-in and day-out above anaerobic threshold is a great way to drive the athlete into over-training symptoms, therefore it must be dosed appropriately. The proper organization of high-, low-, and even medium-CNS intensive stressors is important to keep athletes fresh, fast, and most-importantly, healthy.

It is important to note that the use of small group, individual training, rondos, and small-sided games all allow for the conditioning of musculature used in the specific biomotor demands of the sport. An important addition to just about any field sport is extensive tempo. Extensive tempo allows the athlete to accumulate volume at the highest possible speed (about 70% of max velocity) that is considered a low-CNS training stimulus. This allows a greater frequency of exposure to linear sprint mechanics and preparing the tissues for the stress associated with competition (at high average velocities). This provides the sub-maximal speed reserve.

Just like Coach Holler, my opinion is that if your athletes are happy, healthy, and well-prepared, your program will be successful. The skills required to effectively communicate the goals and expectations of how a program is developed and performed, are of paramount importance. Being an effective communicator with others on the coaching staff as well as your student athletes will ultimately determine the success of any program. The communication makes sure that there are the right people in the right place doing the necessary work.

Andrew Cormier

Instagram: @andrew.cormiaye

Email: [email protected]

Website: sprint-jump-throw.com

As we can see, the average soccer player, and most other field-sport athletes, need to develop tissue tolerance to the external loads that will be placed on their body during competition. In order to develop the game-breaker qualities in speed and power as well as prepare them for all of the low-speed volume required to compete, training must be logically programmed, implemented, and managed. I specifically used the term low-speed volume because that does not mean it is low intensity. From watching a player, instead of just the game, you will observe many times that the athlete will continuously be shuffling side-to-side, slowly backpedaling, or even giving a valet jog while the ball is not close to them, but still maintaining the tactically advantageous position - those could be considered as low intensity because there is no pressure. Most plays made with the ball in which an opponent is directly pressing them require explosive touches on the ball, a few steps into open space, and then executing some sort of pass or shot. Those plays are certainly high intensity, however looking at the GPS data and not watching the player, all you would see is that they completed some sort of movement at 50% of their max velocity.

In small group and individual training in which technical skills are developed it is important that skills are practiced at a high intensity for seven seconds or less and then rest is provided such that the next rep of the skill is at the same quality. The beautiful thing about coaching is that if the skill is not being executed at the highest level, as expected in a game, you can stop the drill, provide feedback and enough rest so that the next attempt can done be at a higher quality. If fatigue is truly the limiting factor you have found your stopping point.

Many coaches utilize rondos and small-sided games for the technical and tactical development of their players. Most of those do a great job at providing the explosive efforts and sub 75% of relative max velocity speed demands required in a game (depending on constraints). The same guidelines can be provided to these drills, meaning that if the quality of the technical and tactical skills are not completed at a game-like level, stop the drill provide rest and feedback, and restart if it is desired. The nice thing about this style of drills is that there is the continuous, “flowy” type of play that is similar to competition.

There is obviously a tremendous amount of value in the development and execution of technical and tactical skills during these games, most even provide a supramaximal bioenergetic demand compared to competition averages. Competition averages are just that - averages. The distance-per-minute of a rondo or small-sided game may be 10 to 20% greater than the competition average, meaning it may actually touch the peak distance-per-minute attained during game for a small period of time. That is important for the preparation as well as the development of the bioenergetic demands of the sport, which certainly raise the heart rate to a point past the anaerobic threshold. Like many of our readers know, continuous training day-in and day-out above anaerobic threshold is a great way to drive the athlete into over-training symptoms, therefore it must be dosed appropriately. The proper organization of high-, low-, and even medium-CNS intensive stressors is important to keep athletes fresh, fast, and most-importantly, healthy.

It is important to note that the use of small group, individual training, rondos, and small-sided games all allow for the conditioning of musculature used in the specific biomotor demands of the sport. An important addition to just about any field sport is extensive tempo. Extensive tempo allows the athlete to accumulate volume at the highest possible speed (about 70% of max velocity) that is considered a low-CNS training stimulus. This allows a greater frequency of exposure to linear sprint mechanics and preparing the tissues for the stress associated with competition (at high average velocities). This provides the sub-maximal speed reserve.

Just like Coach Holler, my opinion is that if your athletes are happy, healthy, and well-prepared, your program will be successful. The skills required to effectively communicate the goals and expectations of how a program is developed and performed, are of paramount importance. Being an effective communicator with others on the coaching staff as well as your student athletes will ultimately determine the success of any program. The communication makes sure that there are the right people in the right place doing the necessary work.

Andrew Cormier

Instagram: @andrew.cormiaye

Email: [email protected]

Website: sprint-jump-throw.com

Proudly powered by Weebly